By Andrew Mulenga

There are a few artists in Zambia that can boast the

consistency of David Chibwe, a painter and printmaker that has been active on

the Lusaka art scene for well over 40 years, surviving on nothing but the coaching

and production of art alone.

|

Akalela dance, acrylic on canvas,

by David Chibwe |

As focused and uninterrupted as his illustrious career

may appear, it started on a rather flippant note when in 1970 as a teenager he

left his parents’ home in Lubumbashi, Congo where his father, a Zambian

missionary lived for many years.

“When I left the Congo I never went to see my

relatives in Zambia, it was an adventure I didn’t even have money for transport

but my friend sponsored me. We arrived in Ndola and were supposed to catch a

train to Lusaka, by then it was 1 kwacha 18 ngwee per passenger but we only had

2 kwacha,” he recalls.

Luckily Chibwe had a box of watercolours, then they

stumbled upon Kingston’s, a popular stationary shop at the time, seeing the array

of brushes, tubes and paper, the excited youths decided to invest.

“I told my friend let’s use the little money we had,

when I convinced him we bought assorted material, and went to sit in the park

next to the museum, we sat on the benches and I started making small abstract

paintings, it was just after new year we were very young and a bit hung-over

from a late night,” he recollects wearing a mischievous smile.

|

David Chibwe working at his home

in Kaunda Square Stage 1, Lusaka, Zambia |

“We sold my paintings for two kwacha each, then we

went to Savoy Hotel, I sat outside and started making some more, my friend was

doing the selling and we ended up making over 30 kwacha which was a lot of

money, we were still in the New Year mood so we went to a bar called the Under

Tavern at Broadway”.

Having had their fun, the lads eventually managed to

catch the train. When he got to Lusaka, Chibwe was able to locate his sister’s

friend in Kamwala who took him in. He wasted no time and started selling, his

paintings in Madras and Long acres.

“I used to sell door-to-door, I made allot of money,

but four months later I went back to Lubumbashi and stayed there for 6 months

before coming back to Lusaka,” he says “But in 1972 I met Edwin Manda, a famous

actor who was also in charge of running the National Dance Troupe under the Cultural

Services Department. He used to take them all over the world to perform but

when he saw my work he gave me a job too.”

It was Manda that offered him a place at the Kabwata

Cultural Village alongside craftsmen but then he [Manda] thought that it was

not the place for the ambitious young Chibwe, who after all had undergone some

formal art training at the Athens Royal School Likasi in 1964, the Academies of

Fine Arts in 1967 and Artistic Humanities Des Beaux Arts, Lubumbashi,

|

Less than a dollar a day, acrylic

on canvas, David Chibwe |

Democratic Republic of Congo in 1969. He was clearly a cut above the rest.

“When Henry Tayali came back from studies in

Germany, Mr Manda introduced me. Also Mr Tayali told me that the cultural

village was no place for me,” he says.

It is Tayali who introduced him to the Art Centre

Foundation (ACF) at the Evelyn Hone College, where he started working with

Patrick Mweemba and Fackson Kulya until they were joined by the Choma-based, Dutch

artist Bert Witkamp, Style Kunda and the youngest member of the group Vincentio

Phiri. In fact in its day, under the leadership of Cynthia Zukas MBE and the

late Bente Lorenz, the ACF was so organized it would host discussions every

Thursday where they would invite and engage non-artists and key members of

society.

“We would

just sit and talk about art, we even used to invite people like medical doctors

and lawyers, so one doctor even gave us a contract to decorate the children’s

wing at the University Teaching Hospital when we convinced him that art is

therapeutic,” remembers the artist.

|

Dance to the rythm, acrylic on canvas,

by David Chibwe |

Chibwe would later become a founder member of the

Lusaka Artists Group which was operating under the Art Centre Foundation, but

he explains the group was short lived because it was like having an

organisation within an organisation.

He remembers the late 1970s and the early 1980s as

being the golden age of art collection in Zambia; these are the days of the

defunct Mpapa Gallery founded by Joan Piltcher with Heather Montgomery, Ruth

Bush, Gwenda Chongwe and Zukas as board members.

“Mpapa Gallery were very strict and they did not

just display anyone or anything, it is not like nowadays at the Visual Arts

Council where the gallery is just showing anything,” he declares taking a swipe

at the VAC run Henry Tayali Gallery in the Lusaka show grounds.

“In the 80s there was also an Indian who came to the

Evelyn Hone College, he is the one who thought of commercialising the artists

workshop he thought we should do silk screen, so we went to Lumumba Road and

from there we started printing seed bags for Zamseed, but this guy was also a

drug dealer he ended up being arrested at Bombay airport and the project died,”

he adds.

|

| Market place, acrylic on canvas, by David Chibwe |

From his tales in the 1980s he also suggests that

when there was a change of government at the turn of the decade those who came

into power were simply not interested in art and this was a serious downturn.

“When the new president and cabinet do not

appreciate art then that’s the end, there are very few Zambian ministers or

even businessmen that can buy a painting from you today, not even for K1, 000

(one thousand kwacha) when you tell them the price they say ah! Even prominent

black buyers like Mr Kapotwe it is just because he worked with Mr Sardanis for

a very long time”, he alleges.

|

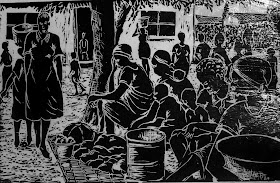

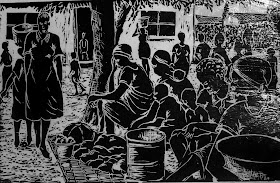

| Vendors, linocut, by David Chibwe |

For the most part, Chibwe has had a very illustrious

career, enjoying significant commissions over the years. His linocut prints and

paintings have been collected all over the world. Perhaps in the evening of his

career, he now intends to retire to a small holding in Chongwe where he will

teach and produce art, known for knocking from door to door seeking funding for

the project proposal intended for an art village he tends to build there. It is

sad to note however, that something does not add up, at 66 he appears to be

older than he should; he is clearly stretching himself to make ends meet as

well as get his project going. One feels he could have done better for himself

than wait until he is not getting any younger and visibly weary, but such is

life. Unlike many western countries that have retirement packages for aging

artists, this is far from being a reality in Zambia.

Nevertheless, Chibwe

remains a maestro, one of the Zambian greats his rhythmic brushstrokes still blend

perfectly with his musical subject matter as can be seen in the paintings Akalela Dance and Dance to the Rhythm. The soft colour palette and mildly blurred

visual effects that lend the artist his signature style will continue to charm

us for ages. He lives and works from his home in Kaunda Square stage 1.