By Andrew Mulenga

But far from the shimmer of over-polished

cars you expect to see at a vintage car show, all the cars in this venue are

rusty non-runners with no tires, holes where their headlamps used to be and

they are all the creation of one of Zambia’s most inventive artists, Mwamba

Mulangala.

In fact they are all paintings in a body of work that opened on Thursday in an on-going exhibition entitled Point Of View.

Nevertheless, viewers must not be fooled by

then artist’s outwardly innate subject matter. There is something deeper to the

work. Over the years not only has he focused on exploration of material, he has

also been thematically consistent on his creative quest to insightfully provoke

thought.

Mulangala’s cue that the cars can be the embodiment of characters or individuals we know or may have known strikes a chord with this author. Having literally grown up in a 1970’s Ford Cortina, and being driven to school every day one feels the incarnation of one’s father in Point of View # 18. Similarly, having convinced ones mother at the age of 10 to spontaneously buy a yellow VW Beetle during an afternoon stroll, yes cars were bought that easily at some point in time, one sees the embodiment of ones mother in Point of View # 7.

Anyhow, as much as he too may have a Point Of View this article is not about the author, it is about Mulangala’s latest body of work. Point of View #3 should be one of the more interesting and collectable pieces of the show, because little known to many, and probably to the artist too, it is the depiction of an old car outside Lusaka National Museum which according to reliable museum staff was used by the iconic freedom fighter Harry Mwanga Nkumbula during Zambia’s liberation struggle. There is no telling what make the rusty old car that rests just next to the fence of the Government Complex is, but it looks like something out of Mario Puzzo’s The Godfather.

A 1930’s Fiat 500 Topolino, a 1940s Austin

12, a 1950s Morris Minor and a 1960s Mercedes Benz 190.This line-up of memorable

automotive icons currently on display at the Alliance Francaise in Lusaka certainly

sounds like what you might expect to see at a classic car show.

| Point of View # 3, Acrylic enamel on metal 45 x 57 cm, 2011, painted after a wreck outside the Lusaka National Museum that is said to have been driven by liberation icon Harry Mwanga Nkumbula |

In fact they are all paintings in a body of work that opened on Thursday in an on-going exhibition entitled Point Of View.

The 36-year-old has toyed with rusty old cars

as subject matter since the late 1990s around the time he became the youngest artist

to ever win a Ngoma Award in the Henry Tayali category at the age of 23.

Recent development in his production is foreshadowed

by a longstanding technique to mimic rust in his depiction of old cars. In his

latest series however, with works simply titled Point of View # 1 and so on, he completely does away with canvas and

uses actual, rusty old sheets of metal that he painstakingly collects from

scrap metal dealers, competing with manufacturers of makeshift wash basins or shomekas as they are called by many

township dwellers.

But where his scrap metal collecting

competitors, the shomeka makers make

it a point to scrape off the rust, Mulangala keeps as much of it as he can giving

his work a realistic, almost three-dimensional finish. And it works. The effect

can be best appreciated on works such as Point

of View #10 which depicts the shell of a hole-ridden 1960s model Peugeot J

7 van.

“I’m very specific on the corrosion of the

metal. I use a different kind of acrylic when painting on rusty metal, its

acrylic enamel. I want the rust to come out, to really show” he explains “On

most paintings I try to make sure that I use 50 per cent rust and 50 per cent

paint. For preservation I apply metal clear coating to stop the oxidation

process and further decay”.

He goes on to passionately explain the text

book theory of rusting metal, reminding us that besides being a professional

artist, he is also a school teacher at the American International School of

Lusaka where he teaches lower and senior grade art.

|

| Point of View # 18, Acrylic enamel on netal 46.5 x 59.5cm, 2012 |

“I have always painted cars. But they can be

connected to personification, their characters can be likened to human

characters, to people you and I may know or may have known individually,” he

elaborates in an impressively eloquent manner. “But the main interpretation is abandonment.

These cars can symbolize anything, talents, things or fellow human beings that

people overlook, or even certain things that you abandon and do not notice in

yourself in introspection.”

Mulangala’s cue that the cars can be the embodiment of characters or individuals we know or may have known strikes a chord with this author. Having literally grown up in a 1970’s Ford Cortina, and being driven to school every day one feels the incarnation of one’s father in Point of View # 18. Similarly, having convinced ones mother at the age of 10 to spontaneously buy a yellow VW Beetle during an afternoon stroll, yes cars were bought that easily at some point in time, one sees the embodiment of ones mother in Point of View # 7.

Anyhow, as much as he too may have a Point Of View this article is not about the author, it is about Mulangala’s latest body of work. Point of View #3 should be one of the more interesting and collectable pieces of the show, because little known to many, and probably to the artist too, it is the depiction of an old car outside Lusaka National Museum which according to reliable museum staff was used by the iconic freedom fighter Harry Mwanga Nkumbula during Zambia’s liberation struggle. There is no telling what make the rusty old car that rests just next to the fence of the Government Complex is, but it looks like something out of Mario Puzzo’s The Godfather.

,+by+Eddie+Mumba.jpg)

+by+Vincent+Maonde.jpg)

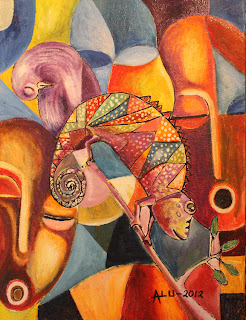

+by+Alumedi+Maonde.jpg)

,+by+Clare+Mateke.jpg)

+by+Suse+Kasokota.jpg)